Revised Common Lectionary Page for 13 February 2011 (Sixth Sunday of Epiphany, Year A)

Revised Common Lectionary Page for 13 February 2011 (Sixth Sunday of Epiphany, Year A)

Deuteronomy 30:15-20 or Sirach 15:15-20 • Psalm 119:1-8 • 1 Corinthians 3:1-9 • Matthew 5:21-37

I readily acknowledge that I think about particular sins in ways that offend some of my fellow Christian teachers. The “all sin is the same in God’s eyes” riff is so common that I wouldn’t even try to narrate its history; it just seems to be written in the collective memory of evangelicals, in that same spiritual book as the assumption that the final judgment of the quick and the dead is going to hinge on whether one has looked at a dirty picture or confessed the sin of looking at dirty pictures more recently at the moment of death. As years have passed, though, I’ve abandoned the rhetorical strategy of examining the philosophical assumptions of folks who assert such things and have tended, in recent encounters with the “all sin is the same” camp (I’ll leave the hairy-palmed final judgment for future musings) to answer with a couple questions about the text of the Bible that usually at least send the one asserting back to the text of Paul to make sure what’s assumed there is in fact there.

The questions are not hards ones: Did the law of Moses come from God? If so, does the law of Moses prescribe different punishments for different sorts of misdeeds? If so, then does what came from God at the very least imply a distinction between sins? Someone at least marginally familiar with the Bible (and someone with as much honesty as one of Socrates’s interlocutors–which is to say more than someone on a 21st-century political talk show) will answer yes to all three, and hopefully answering yes to all three will invite such a person to revisit the context of some of Paul’s most-paraphrased assertions.

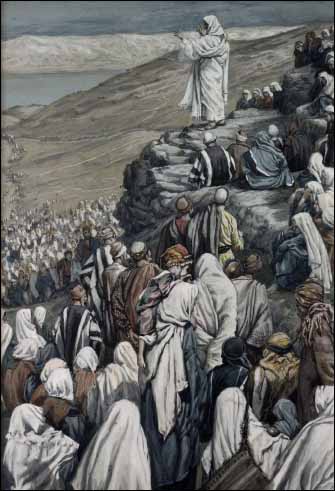

This week’s gospel reading really only makes sense if sins happen in the context of the Church, the city on the hill about which Jesus preaches earlier in Matthew 5, and therefore, the one committing sin seems to matter just as much as the content of the act that sometimes gets called a sin. After all, Jesus among all people seems to recognize that the relationships among the people who are part of that city and the relationships between those who are not differ somewhat. Luke 11 and Matthew 23, for example, have Jesus calling people fools, which would at least on the surface indicate that the word “fool” itself is not the issue. And with regards to oaths, Revelation 10 has an angel of the LORD swearing an oath to the people of the earth. Whatever is in fact going on in this section of the Sermon on the Mount, it appears to be something other than universal moral instruction.

The nice thing about such a realization is that reading these teachings as constitutional and ecclesiological ultimately makes more sense of them than does the “Bible as instruction book” or even the Martin-Luther-flavored, “doesn’t this just make you feel awful” approach. Jesus is, after all, continuing his oration about the people gathered around him as the city on the hill, the light that illuminates the world and invites people to goodness. Given the radical proposition that living people can be the ideal towards which nations strive, it makes perfect sense to say that, among those who light the world, one member of that body should not brand another with the label “fool” (more a term of moral inferiority than intellectual, at least in the Proverbs tradition) but should see to it that the young (which is not synonymous with foolish) are instructed for the sake of bringing them along in maturity. And in a community that will sing of YHWH as a groom and themselves collectively as the bride (a carryover from Israel’s prophetic imagery, of course) should not idly condone men’s leering after women’s bodies as if the allegory didn’t completely redefine the relationships between men and women among the light-city. And certainly that redefinition of men’s and women’s lives together should call into question the ease with which a man issues a legal document and thus leaves the woman to whom he’s been joined as a functional widow. Finally, for this week’s gospel reading at least, a community that exists together as the body of the King should not require oaths to support assertions–the legal structures that enforce truth-telling upon penalty of the law should be unnecessary if in fact the city is functioning as light for the world.

All of these things Jesus calls for in the context of the faithful, for the sake of being salt that gives flavor, expecting that the community will adhere to them not for the sake of their own glory or to make the world around them less wicked but precisely in order to cast light and therefore judgment on the assumptions that drive the system that John would call cosmos (world). To expect that all people should or would adhere to these things is to neglect the relationship that Christ posits between the nations and the faithful, between the proclamation of the kingdom and the reception of that proclamation. In Paul’s context, dealing with Corinthian Christians who treat Paul and Apollos and Peter as competing sophists, one group running after each as if philosophy (which is by its nature contentious) and Christ (who is by His nature one body) could adhere to the same way of living in the same place, the call to imagine the community as one edifice (and thus to define common life as edification) reminds the Corinthians that something new has in fact happened. No longer is the rhetorical life a matter of seizing and maintaining power over another person (as the sophists did by their words and as Alexander and later the Romans did by force of arms); now the aim of all words is to proclaim the Word, both the incarnate logos who is Jesus of Nazareth, Son of God; and the divine rhema, the powerful proclamation that all things are made new. It’s not that God likes you or me less when we engage in such divisions or lusts after our neighbors’ spouses or swearing of oaths to secure rhetorical advantage; on the contrary, God’s favor was given and will always be given, standing as gift in every moment. No, the point here is that the content of that gift is to be City-on-the-Hill, to build one another up, to experience a mode of human life that strife and contention simply can’t offer. We heed the Sermon on the Mount not in order to convince God that we deserve the gift but because it is itself God’s gift.

May we Christians be thankful, not that God has overcome the words of Christ but because God has spoken them.

Great post–especially the final point about it being God’s gift.

Very healthy and sound conclusion of how the city on the hill is a gift in which we “build one another up”. It should humble us to keep in mind that the best of citizens in this city have their moments of failure that are greater than those outside of it. For this, our hope should be to encourage each other to be more, while forgiving one another’s times of being less.

We hear so much from those around us in our daily routine about the hypocrisy within the church. However, the hostility shown by those outside the city toward Christians, especially a fundamentalist, when his or her secret life is found out, is not so much what the Christian was doing, as much as it is the attitude, “I just have a weakness; I’m not like you”.

We should not simply disregard this hostility as typical anger of non-believer toward believer. We usually create what they see and how they see it. And if we just talk to them and pay attention, they will let us know, in their own way, that there is a city on hill they stand in awe of; it is the one in which its citizens have no fear of saying, “We are like you”. I believe it is then that they see how imperfections create the glow of mercy.